Maja and Reuben Fowkes

During the bygone era of the post-1989 cultural compromise, the Hungarian art world was characterised by a basic professional consensus and while the scene was divided into competing camps, thesereflected differing artistic visions rather than opposing political ideologies.

Since the FIDESZ government came to power in 2010, there has been a concerted attempt to shake up the cultural establishment as part of a rightwing campaign to complete the job of dismantling the remnants of the socialist system and return to the national values of the pre-communist era. The unfolding of this strategy is having a profound effect on the cultural sphere, with the contemporary art world as we know it facing a real struggle for survival. As the hurricane edges closer, with reactionaries poised to take control of the institutional landscape of the art scene, habitually noncommittal group ings of artists, curators, art historians, students and even gallery owners have been forced to face up to the imminent threat to their way of life.

While the situation in the Hungarian art scene has now reached an existential tipping point, the storm has been brewing for more than two years. Early skirmishes took place over the appointment by ministerial decree of Gábor Gulyás as director of the Mûcsarnok or Kunsthalle after none of the shortlisted candidates for the job were deemed politically suitable back in January 2011, followed by outrage over a propagandistic exhibition of Hungarian national heroes to glorify the new FIDESZ constitution or Basic Law held at the Hungarian National Gallery. A scandal also erupted over the fusion of the very same

museum with the Museum of Fine Arts, which was announced without a shred of public consultation in October 2011 and realised the following autumn, while a wishful scheme to move several institutions to a brand new museum district near City Park has been met with incredulity. There have also been serious scares over the future of the legendary Liget Gallery and a long drawn out struggle over who should run the pivotal Trafó House of Contemporary Arts, both cases in which the successful mobilisation of professional opinion led to quietly-celebrated tactical victories against political interference

in the arts.

When a late night sitting of the Hungarian Parliament in July 2011 voted the Hungarian Academy of Arts (MMA) into law, turning a civil association originally headed by the doyen of organic architecture Imre Makovecz into a public body with far reaching powers to interfere in the running of the art world, there was little immediate reaction.

It was in fact only in autumn 2012 that the significance of the changes became clear, when the government announced plans to provide the Academy with an austerity-busting budget of 2.5 billion forints, along with ownership of the Mûcsarnok, the country’s most prominent art venue, with effect from 1 January 2013. In addition, the ultra conservative Academy will have a say in the awarding of scholarships and prizes, appointments to art and the power to influence the decisions of the NKA or National Cultural Fund, the main

source of arts funding in Hungary. Extraordinarily, there are even plans for an MMA-run Institute of Research in Art Theory, to be established this summer in downtown Budapest, indicating that the takeover has ambitions to purify Hungarian art history as well as contemporary art.

The strange reality of the MMA burst into public consciousness in November 2012 like a YouTube clip gone viral, with the bizarre spectacle provided by its president, György Fekete, becoming an instant source of seditious humour. Along with his arcane appear –

ance – he sports a distinctive self-trimmed haircut unchanged since the 1950s, comments made since he was thrust into the limelight, including veiled anti-Semitic jibes disputing the Hungarianness of writer György Konrád and his view that the criteria for membership of the MMA should include a clear sense of “national duty“, have turned the octogenarian ultra nationalist into a figure of fun for the opposition, who printed a range of Fekete masks to be worn at demos.

Like a dreadful throwback to the Kádár era, the ranks of his new Academy are dominated by old, forgotten faces, many of whom one suspects have swallowed any misgivings they might have about Fekete’s cultural agenda for a poverty-beating monthly stipend

payable to all 250 full members.

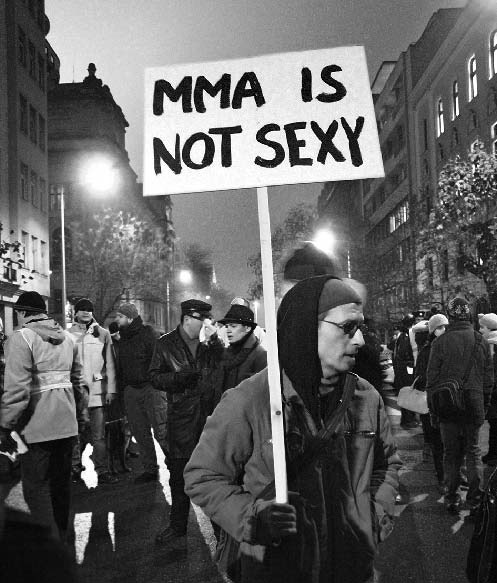

The announcement of the plan to hand over the Mûcsarnok to the MMA sent shockwaves through the art world and has driven many politically-reserved art professionals to protest. Along with an online petition, a protest letter from the Hungarian branch of the International Association of Art Critics (IAAC), and another from the Studio of Young Artists (FKSE), the Hungarian art world has responded with direct actions that put the interventionist strategies of public art to good effect. These have ranged from an action to declare the Mûcsarnok to be a site of national remembrance in a candle lit ceremony,

to organising a Gangnam style protest on the steps of the building with gallery owners and the former director joining the dance and linking up with student protesters, carrying media-friendly conceptual banners such as “the MMA is not sexy“.

The most successful direct action was also the most courageous and involved a group of Free Artists gate-crashing the annual meeting of the Academy on 15 December 2012 and attempting to unfurl a protest banner across the podium that read “The MMA is exclu –

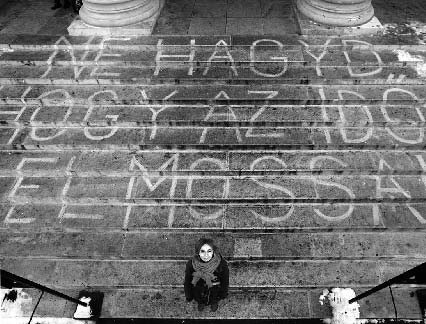

sion ary, art is free“. This was immediately met with a degree of brutality and intolerance that would be out of place in any normal art setting, with the press on hand to document the forcible ejection of the demonstrators from the meeting. The most dramatic image, which shows artist Csaba Nemes having his face squashed by a portfolio, has itself been memorialised – as if for a future iconography of the protest movement once victory over the MMA is achieved – in a drawing based on the original photograph. Further artistic protests directed against the MMA takeover include the curatorial project Stand Out Every Week that invites an artist to make an intervention in front of the Mûcsarnok, with Emese Benczúr’s gesture in chalk “Don’t let time wash it away“ bearing witness to the imminent threat facing contemporary Hungarian art.

The struggle for control of Hungarian art has brought the professional art world face to face with a group of malcontents who until recent ly it was safe to completely ignore. From one angle, what is happening is the revenge of those who in the past felt hurt and sidelined by mainstream galleries and excluded from government funding, a lumpenproletariat of provincial Sunday painters who finally have the chance to turn the tables on the metropolitan intellectuals, storming their elitist citadels to impose their own version of artistic culture. However it’s not just the ultras from the MMA that the progressives

have to deal with now, but also a substantial rump of fellow travellers within the art world who for opportunistic reasons have decided to dance to the government’s tune. That the political fault line running through Hungarian society also divides the scene was shown by the number of people who signed a petition in support of Mûcsarnok director Gábor Gulyás after his half-hearted resignation or who participated in his summer 2012 show Mi a Magyar? (What is Hungarian?), which clearly pandered to official ideology, at a time when the majority in the local art world were boycotting the Mûcsarnok in protest at the way he was appointed.

It is perhaps worth noting that the return of Viktor Orbán’s distinctive brand of rightwing politics to centre stage in Hungary also coincided with the onset of the age of austerity, which has brought significant changes to the tone and self-image of globalisation. Within the art world this is manifest in the sentiment that contemporary art, as a recognisable genre of artistic production associated with the rise of biennial culture and the mutual appreciation of the profits and possibilities of globalism, may actually have come to an end in 2008 when the bubble burst. Within Eastern Europe, the previously dominant discourse of transition suddenly evaporated, with the direction of the collective journey and the ultimate destination appearing less sure than at any time since the fall of communism. The cultural upheaval in Hungary also reflects this process of reorientation away from a model of globalisation based on the free flow of capital with no concern for social or environmental impacts, although the nationalist identitarianism proposed by regime apologists has nothing in common with the agenda of the counter-globalisation movement.

While the post-89 cultural compromise was broken by the right, there are now a growing number of people in the Hungarian art world who are demanding not a return to the previous status quo, but the creation of something better. Issues that are up for discus –

sion range from reform of the procedure for appointing museum directors to the long overdue renewal of art education, which is still very much weighted towards traditional subjects, rather than preparing students for a future in contemporary art. Perhaps the most sensitive issue is how to achieve a reorientation of the institutional focus of the arts away from a preoccupation with the national frame towards a more internationalist and cosmopolitan outlook. At the time of writing, it is still unclear whether the Hungarian art world, which has suddenly found its voice in opposition to the potentially disastrous changes promised by the MMA, will succeed in defeating this “cultural putsch“ in the short term. However, at the end of the day all the best arguments are on the side of free art.

MMA countdown – Free Artists welcomes the resigned MMA-members!

MMA countdown – Free Artists welcomes the resigned MMA-members! TRANSZPARENCIÁT!

TRANSZPARENCIÁT!